Article submitted by Mike Stinson, CCIM, Sales and Leasing Agent for Saurage Rotenberg Commercial Real Estate

Written by Christopher H. Volk for CIRE Magazine | November/December 2016

Most businesses that rely heavily on real estate in their day-to-day operations prefer leasing to ownership for managing their real estate locations. Among the many reasons for this preference are the cost of capital and corporate flexibility.

As a result, investor ownership of real estate leased to businesses represents a large and growing long-term, income-oriented global investment class. These net lease investments allow landlords to be passive recipients of what they expect to be predictable long-term, income-oriented returns.

A common investor perception is that such return predictability can be elevated by investing in real estate leased to high credit quality tenants. In turn, high credit quality companies have responded, offering a bounty of leased real estate to individual and institutional investors estimated to be valued well in excess of $1 trillion.

Just a glimpse of this market shows smaller free-standing properties leased to investment grade companies and held by investors were estimated to have a combined value well north of $500 billion in 2014. To place this $500 billion subset of the broader net lease market into context, this amount is about five times the combined enterprise values of publicly traded U.S. REITs, which invest in such types of leased assets. With such a broad investor demand for real estate leased to high credit quality tenants, it makes sense to examine the degree to which corporate credit metrics govern net lease real estate investment risk.

Dispelling Prejudice

During the past few years, real estate analysts and investors have answered which they would prefer: investing in a store leased to Home Depot or a store leased to an Ashley Furniture licensee. Home Depot wins, hands down.

However, the question is unfair because not enough facts have been provided. Still, the sheer number of people who prefer Home Depot as a tenant shows a prevailing presumption. Most respondents presume that everything else is equal and that all they have to decide on is the preferred tenant. They want the better credit, so they choose Home Depot.

Those who know more about real estate and real estate leasing understand that the leasing playing field is not equal.

Real estate leases are simply contracts that each come with certain landlord rights, and wide diversity exists among net-lease contracts. Of course, tenant credit quality is a key component of lease contract risk, but it is far from the only consideration.

An investment grade company, such as Home Depot, is very likely to pay the rent it owes over the next few years. Investors, however, should concern themselves with more than just the short run. They should pay attention to the ability of the contract to perform well over its entire lifespan, which is often 10 years or longer.

When considering the longer-term risks, various considerations come into play. Foremost is the price a landlord pays for the real estate.

If the asset becomes vacant, how much is the downside risk? It turns out that it is common for real estate occupied by investment grade tenants to sell for considerably more than it costs to create. It also turns out that it is typical for real estate that is leased to investment grade tenants to have rents that are well above those in the local marketplace.

Binding Multiple Tenants

Another issue is the availability of master leases. Master leases are an institutional investor creation and are basically a single lease that binds multiple tenant properties. Their value lies in tenant alignment of interest. Having a single, or master, lease across multiple properties allows for locations to be aggregated. So if a tenant falls on hard times, master leases are more likely than not to prevent tenants from cherry-picking properties or retaining only select locations within a bankruptcy.

That is because tenants generally have to treat a master lease in bankruptcy as a single contract that is not divisible into multiple contracts. Unfortunately, master leases are generally not available from investment grade companies.

In the case of profit-center property, investors should know exactly how profitable the business at each location is to assess this lease-rejection risk. That would be another desirable contract feature: unit-level reporting of profit and loss statements for profit-center properties. Here, it turns out that it is unusual for investment grade tenants to agree to provide unit-level reporting.

The small print in leases is also important. Other contract issues that pertain to investment risk include whether the lease is signed by the tenant or its parent company; lease term (longer is better); the extent of landlord obligations; the ability to shut down the location without landlord consent; assignment rights to ensure the tenant stays liable for the lease obligation; subletting rights to be sure that any subtenants can be easily removed if the lease defaults; condemnation clauses; and environmental risks.

As to the small print, a landlord should know one important fact: it is commonplace for investment grade tenants to write their own leases.

All of a sudden, the Ashley licensee is starting to look a lot better. And then the question comes into clear focus: how important is the credit quality of my tenant, anyway?

Deceiving Statistics

Across the U.S., about 18,500 companies have revenues of more than $300 million. This includes multiple types of companies – from electric utilities to banks, to insurance companies to REITs, and industrial to retail and service companies. Of all of these businesses, only 3,120, or 16.9 percent, were even rated by Standard and Poor’s in 2014.

Investment grade credit ratings start off at BBB- for Standard and Poor’s and Fitch Ratings and at Baa3 for Moody’s. As of 2014, less than half of all of Standard and Poor’s rated U.S. companies had an investment grade rating. The result is that more than 92 percent of companies with more than $300 million in revenues have either no rating or a rating that is below investment grade.

The foremost reason for this big percentage is that approximately 83 percent of large companies elect not to be rated at all. Their choice generally reflects a corporate preference, rather than a reflection of their comparative credit quality. Businesses simply have credit options available that do not require them to have corporate credit ratings.

Of the approximately 1,400 U.S. companies rated investment grade by Standard and Poor’s in 2014, very few made the list of favored investment grade tenants. These tenants are defined as real estate-intensive businesses that employ numerous smaller, free-standing real estate locations.

In fact, Standard and Poor’s rates just 36 such companies and Moody’s rates 33. The highest-rated company today is Walmart, which is rated AA by Standard and Poor’s and Aa2 by Moody’s.

The first question an investor might ask is, “How likely is it that a corporate credit rating will last?” It turns out that corporate credit ratings can be fairly transitory.

Evaluating Probabilities

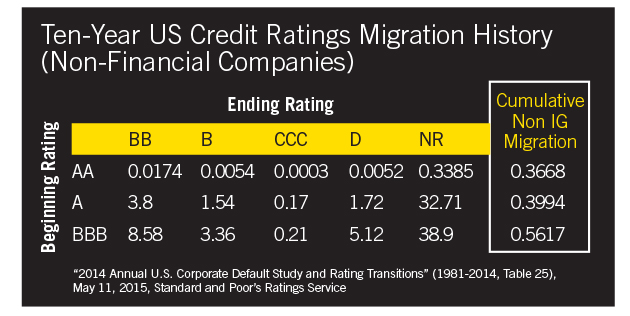

The Standard and Poor’s 2014 “Annual Global Corporate Default Study and Rating Transitions,” published in 2015, showed significant 10-year credit migrations for nonfinancial companies. The credit migration table is shown in Chart below.

If investors lease an expensive property to an investment grade tenant at a low investment grade tenant type of lease rate, the 10-year credit migration table might give them pause. And if investors look at the list of favored investment grade companies, more than two-thirds of their ratings are in the “BBB” area, where the probability of migration to below investment grade is about 56 percent during 10 years. Now, many leases extend for more than 10 years, which will meaningfully raise the likelihood that the tenant will no longer have an investment grade rating at the conclusion of the primary lease term.

Given that most real estate investors employ seven- to 10-year secured borrowings to acquire properties, tenant credit downgrades can have a definite adverse impact on the ability to refinance these assets.

Most of the downward migration movement across all investment grade ratings is to nonrated status. It is a corporate choice to join the 83 percent of nonrated larger companies. Of course, the credit migration table is a historic table that includes the Great Recession.

I think that in the future, however, migrations are likely to be the same or higher. This is because many investment grade companies are laden with real estate, which subjects them to activist shareholders who would prefer to see them with smaller, more efficient balance sheets.

Also, given that the number of retail and service companies is likely only a small portion of the nonfinancial universe evaluated by Standard and Poor’s, I surmise that the ratings volatility of such companies is likely to be even higher. In the end, public companies are run to benefit their shareholders, not their creditors, and their boards of directors will elect to do what they believe best for shareholders.

Evaluating Credit

The news recently has told me a lot about the notion of tenant credit migration. My career began as a credit analyst, and I have long known that corporate credit can be both volatile and transitory.

Credit quality can change because corporate business models that were once potent become functionally obsolete. Think Circuit City, the once-large appliance and electronics retailer that filed for bankruptcy in November 2008 and then shuttered all of its locations, or Borders Books, which disappeared not long after filing for bankruptcy in November 2011.

Most often, creditworthiness changes because of corporate strategic or capitalization decisions. Leadership simply abandons the credit status quo and opts for a new paradigm.

As is shown in the credit migration tables, most downward migration is comparatively orderly and not due to insolvency. But insolvencies do happen, with most businesses able to reorganize. From the vantage point of landlords and creditors, corporate insolvencies can come on quickly from once-investment grade ratings.

In 1990, Circle K, which was then the nation’s second-largest convenience store chain operating 4,631 stores in 32 states, filed for bankruptcy protection. A few years earlier, I had personally visited the investment grade retailer, which had a preference for leasing its stores.

However, the company declined to share unit-level profitability with landlords or the actual cost to construct its stores. I was told not to concern myself with these details, since the company, which was investment grade, would be fully obligated to make the lease payments. Such lack of transparency ultimately proved harmful to their many landlords.

Later, Kmart, a leading discount retailer, was rated Baa3 by Moody’s, with a stable outlook up to April 2000. Less than two years later in January 2002, the company filed for bankruptcy protection. Kmart emerged from bankruptcy after shedding approximately 300 unprofitable stores.

Unfortunately for the landlords, they had no advance warning, as the leases did not provide them with any unit-level financial reporting. They thought that their rents were being paid by the “credit” (the company).

Discovering Valuable Lessons

In bankruptcy, with unprofitable store leases either rejected or renegotiated, the landlords learned an important lesson. The rents actually came from the profits of the stores that they owned, and the “credit” was only worth something if the tenant was solvent. The landlords would have made far better investment decisions if they had understood the profitability of the stores that they owned.

George Bernard Shaw was unfortunately right. History repeated itself, and new generations of investors did not learn from their predecessors.

Look for Part II of this article to be published in the 2017 January/February issue of Commercial Investment Real Estate.

Mike Stinson, a native of Monroe, Louisiana, is a graduate of Louisiana State University (LSU). A real estate licensee since 2004, Mike specializes in the sale and leasing of commercial real estate. A Designee member of the Certified Commercial Investment Member Institute (CCIM), Mike’s other professional memberships include Baton Rouge’s Commercial Investment Division (CID), the LSU Alumni Association, REALTOR Land Institute (RLI), and an affiliate member of the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR).

Saurage Rotenberg Commercial Real Estate is a member of the Baton Rouge Area Chamber of Commerce (BRAC); the West Baton Rouge Chamber of Commerce; the Baton Rouge Better Business Bureau; the Louisiana Commercial Data Base (LACDB); and the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC). Several agents, on an individual basis, are members of the Society of Industrial and Office Realtors® (SIOR), the Certified Commercial Investment Member Institute (CCIM); the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR); and the Greater Baton Rouge Association of REALTORS® Commercial Investment Division (CID).